Figurative Language 101: Mastering the Metaphor

The Fundamentals of Figurative Language Collection — with Kelly Grace Thomas

Figurative Language: The Quickest Way from Idea to Impact

Hello, Forever Workshoppers! Welcome to the Crafting Fierce and Flawless Figurative Language collection.

In these weekly lessons, we’ll explore what makes figurative language impactful and memorable using examples from contemporary and classic literature.

Then we’ll put these techniques into practice with easy and actionable writing exercises to craft unforgettable metaphor, imagery, hyperbole, personification and symbolism in your work.

And by the end of August, you’ll have a solid foundational range of figurative language to use in your writing.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Week 1 (Today): Figurative Language 101: Mastering the Metaphor

Week 2: 5 Ways to Craft Vivid Imagery (and 5 Common Mistakes to Avoid)

Week 3: How Much Is Too Much? A Balanced Guide to Hyperbole & Personification

Week 4: Use These Symbolism & Sonic Techniques to Make Your Writing Memorable

Today’s lesson is free to all subscribers, so keep on reading. And to access the full Fundamentals of Figurative Language Collection…

Why Use Figurative Language?

Over my twenty years of writing and teaching, figurative language has been one of my favorite subjects to teach, largely due to its imagination, impact, and immediacy.

In an instant, the right metaphor can place you in the speaker’s shoes. An image can haunt you for the rest of your life (that grandfather clock in Stranger Things, anyone?). Personification can revive a sentence that was previously flatlining.

Figurative language isn’t just a tool; it’s a transporter and translator. Notice that I'm using metaphor right now to build a bridge between ideas. Figurative language is embedded in our thoughts, feelings, and everyday dialogue.

Why? Because it is the quickest way to close the gap between idea and impact, writer and reader. Figurative language allows us to relive the richness of someone else’s experience. To take their understanding and tether it to our own. In other words, it provides human connection, in writing and in life — what’s more important than that?

I’m so excited to get started, but first…

A quick introduction:

Hi new friends! I’m Kelly Grace Thomas, poet, writer, coach, and an ocean-obsessed Aries from Jersey. I teach poetry courses year-round through my Substack, The Poetry Coach, and I have the coolest job: helping poets, fiction writers, and essayists bring their words (and books) into the world as a writing coach.

I’m the author of Future Tense (forthcoming from Alice James Books, 2026) and Boat Burned (YesYes Books, 2020). My poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Sun, The Adroit Journal, 32 Poems, Los Angeles Review, Sixth Finch, and elsewhere. I’ve also written three poetry craft books, which are currently taught in high schools across California, including those in the Los Angeles Unified School District. My screenplay, Magic Little Pills, won Best Feature at the Atlanta Comedy Film Festival. I received my MFA from Randolph College, as a Blackburn Fellow. I live in California, where I’m currently working on my third novel. You can view more of my writing at kellygracethomas.com or on Instagram @kellygracethomas

More than anything, I love demystifying the craft — without killing the magic. And I’m so excited to chat with you about how to craft fierce and flawless figurative language. So together, in these workshops, we will focus on the “how” without losing the “wow.”

Sound good? You ready? Awesome.

What Is Figurative Language?

Figurative language is language that conveys meaning in a way that differs from the literal. In other words, figurative language is an interpretation, not a fact or something that can be proven, not something that is logically true. However, figurative language does make things feel emotionally true because figurative language is based on relationships, on showing how one thing represents another.

Example: The spilled milk of moonlight flooded the room, reminding us it was already too late, and our other lives were waiting.

Literal meaning: The moon is made of actual milk, from a cow, which is now spilling into the room.

Emotional meaning: The moment feels like it will be ruined. The night is here, and the speaker needs to pull themselves away to get back to their normally scheduled life.

Now let’s look at the types of figurative language we will be working with over the next four lessons.

Types of Figurative Language

Throughout this workshop, you will deepen your understanding of figurative language through detailed definitions and examples. For now, let’s establish basic definitions for the terms we will be discussing and applying to our work.

METAPHOR:

Compares two unlike things to show a relationship without using “like” or “as”.

Language is a house on fire.

— Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic

IMAGERY:

Visual description that creates a mental picture in the reader's mind.

Her dress billowed in the wind

like a flag surrendering to summer.— Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem

SENSORY DETAIL

An evocative description using the five senses (sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch).

The metallic smell of blood mingled with the sweat on his hands.

— Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games

PERSONIFICATION

When nonhuman objects are given human actions, qualities, and characteristics.

The city stretched itself awake, its streets yawning with the first light of morning.

— Angie Thomas, The Hate U Give

HYPERBOLE

Extreme or extravagant exaggeration.

I’m so tired I could sleep for a hundred years

wake up, and still need a nap.— Roxane Gay, Hunger

ALLITERATION

The repetition of similar consonant sounds at the beginning of words.

We used our words we used what words we had

to weld, what words we had we wielded, kneeled,

we knelt. & wept we wrung the wet, the sweat.— Franny Choi, The World Keeps Ending and The World Goes On

ONOMATOPOEIA

When a word imitates how it sounds — like a "buzz," "bang," or "pow".

The beat drops: BOOM.

— Elizabeth Acevedo, The Poet X

Alright, now we have working definitions and a clear scope of what we will be discussing. Time to craft some fierce and flawless figurative language.

First stop on the tour: metaphor.

Mining Metaphor: Precision, Power & Poetic Muscle

Ready to take your reader from 0-60 in a matter of syllables? To succinctly reshape their understanding of the circumstantial or emotional landscape? Enter metaphor.

As we mentioned earlier, a metaphor is a comparison of two unlike things to illustrate a relationship. Simile does the same thing, but using “like” or “as”. For clarity, when we speak about similes, they are often referred to under the umbrella of metaphor, as they are a type of metaphorical language that makes an intentional comparison.

How Metaphors Are Built

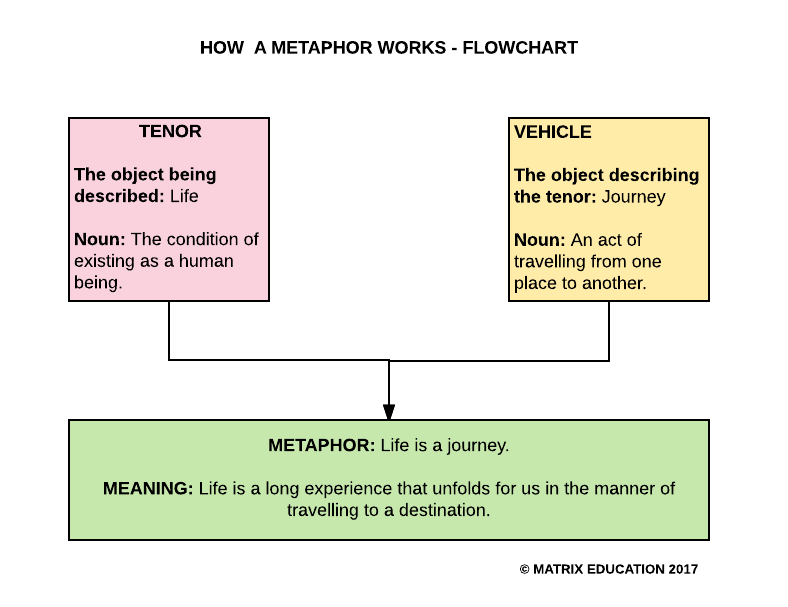

A metaphor has two parts: the tenor and the vehicle. The tenor is the subject to which attributes are ascribed. The vehicle is the object whose attributes are borrowed.

Why is Metaphor Important?

Metaphors build a world we can touch, smell, and taste, offer emotional pitch, provide gravity to define the laws of the poem, and refine our understanding to say this was like that. And through that comparison, we enter the experience with added clarity.

Metaphors allow readers to do something they love to do: participate. The more a reader is involved in a piece, the more memorable it becomes. Metaphors echo long after we have finished the poem or prose.

For example, if I’m writing about the challenges of a certain age, I could state it literally.

Literal: I don’t know how to handle this time in my life.

Effect: While this is straightforward, the end result doesn’t ask the writer to feel, draw conclusions, or participate in the feeling. It is also not specific to what “this time in my life is” refers to.

If I use a metaphor on the other hand…

Metaphor: I don’t know how to dress for the weather of my forties. Healing and health scares and second acts.

Effect: The reader now understands that the speaker is dealing with the unpredictability of middle age. Just like weather, it changes constantly, forcing her into new problems and patterns. Notice there is also a line of literal meaning which pushes the metaphor even further. (We will talk more about this later in the lesson).

When it comes to metaphor, most of our tenors are already predetermined. They are the subjects we write about, including our characters, the setting, and so on. It is the vehicle that we want to make fresh and new. Find the right vehicle and you will have the reader racing to the next line.

Before we dive into each technique and explore all the ways to craft fierce and unforgettable language, it would be beneficial to discuss when and why metaphors sometimes don’t work.

Common Flaws with Metaphor

FLAW #1: Lacking Context

Excellent writing is a cocktail with perfect ratios. Too much literal, it can read flat. Too many metaphors, and we have trouble anchoring ourselves in the poem or passage. Readers must understand the context for the metaphor to have an impact.

Example: It was the summer I swallowed storms. Hurricanes and tropical depressions are making a home inside me.

In this line, the reader has no idea what the storms are supposed to represent. They can assume they are not good, but that’s about all we know.

SOLUTION: Add some context, let the reader in on the literal stakes, setting, and circumstances, so they can echo against the metaphor.

Rewrite: I was only sixteen when I found the vodka. I spent the summer holding back tears, swallowing storms. Hurricanes and tropical depressions making a home inside me.

FLAW #2: Mixed or Overloaded

Because metaphors are so much fun, writers sometimes overdo them. Just like a piece of accent jewelry, a little goes a long way — so does metaphor.

When wearing jewelry, you might not want to mix silver and gold, plastic and diamonds. You also don’t want to mix metaphors, which can send your reader in several different directions.

When writing metaphors, ask yourself: Do these metaphors belong in the same outfit? Am I over- or under-accessorizing?

Example: His heart was a sinking ship. A clock without hands. A tree losing its leaves. A church where no one prays.

In this example, we have references to boats, time, seasons, and faith. It feels like too much for the reader to sink their teeth into.

SOLUTION: Often, one metaphor is enough to capture the reader's focus and evoke emotion. If that single metaphor doesn’t feel like enough, you can use language related to it to extend that metaphor.

Rewrite: My heart, a church where no one prays. Lonely pews and smudged stained glass.

FLAW #3: The Logic Doesn’t Add Up

While metaphors are not to be taken literally, the logic of the metaphor still needs to work — meaning the tenor and the vehicle need to point back to something that can actually happen.

Example: The egg, like a tiny moon, falls into the heat of the frying pan and dies.

While this image suggests that something is being destroyed, eggs are pasteurized, so they are not alive when we cook them. They are technically already dead. Therefore, the metaphor doesn’t work.

SOLUTION: Have the metaphor do something that makes logical sense. Think about what else the eggs can do besides die that feels both logically and emotionally true.

Rewrite: The egg, like a tiny moon, falls into the heat of the frying pan and breaks.

FLAW #4: You’re Using it as a Safehouse

Metaphors can feel like the perfect safe house when we are writing about something personal. We are scared to come out and say something directly, so we use metaphors to dance around the subject. While it is always fun (at least to me) to make something more poetic, it can be confusing for the reader, and they can often feel that you’re avoiding the topic.

Example: Lost without a compass. I wander in the forest looking for a map back to myself.

SOLUTION: Add a line of context where we can fill in some of the blanks of the story. Without context the metaphor falls flat.

Rewrite: I’m not sure how to navigate the terrain of my forties. Mortgages and middle age. The constant tyrant of time. I go to the woods, wander the forest, looking for a map back to myself.

FLAW #5: Cliché or Idiomatic Metaphors

One of the primary reasons metaphors can feel weak is that people often reach for ones we have already heard. These are your typical clichés. Time is money. The world is your oyster. He’s a lone wolf. We’re also used to worn-out idioms: kick the bucket, spill the beans, break a leg. Both clichés and idioms make for weak and expected metaphors.

Example: Love is a red rose.

SOLUTION: Think about what you want to say about the subject and see if you can say it in a way that feels relevant to the concept (in the same family of ideas) using a fresh approach we haven’t seen before.

Rewrite: Love is a dandelion, flower, or weed — just depends on who you ask.

Now that we have reviewed some mistakes to avoid, let's look over some ways to…

Craft Fierce & Flawless Metaphors

#1. First Choice, Worst Choice

Our brains are problem solvers; their goal is to get us out of danger as fast as possible. So when we want to write, “her eyes sparkled like…” our brain is yelling, “diamonds, write diamonds!” It’s trying to solve the problem quickly.

The best metaphors usually take a push beyond the low-hanging fruit. They are unexpected. They sucker-punch you, but you thank them anyway.

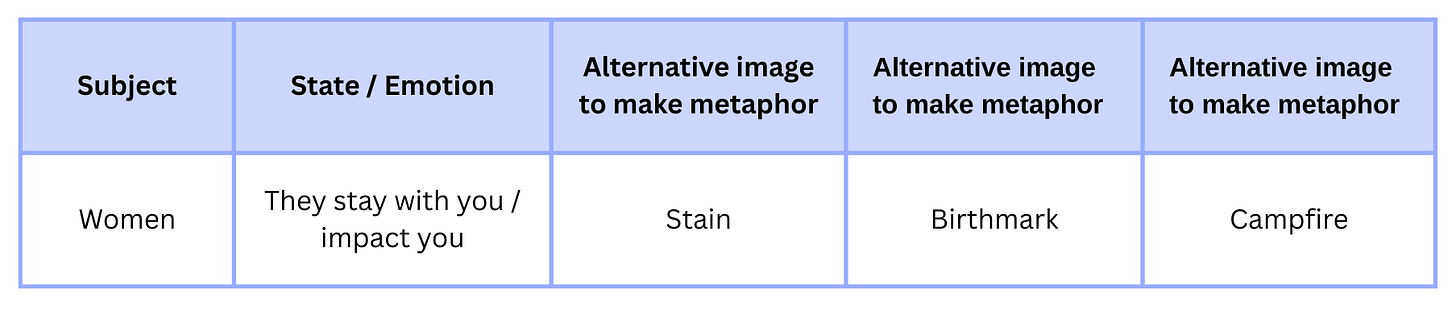

With first choice, worst choice, try to push past your initial thought, to really think of the state you are trying to describe, to come up with some new options. See below.

Example: And the woman said, watch the way we become campfire, how you can’t scrub out our smoke.

#2. Metaphor Mash-up

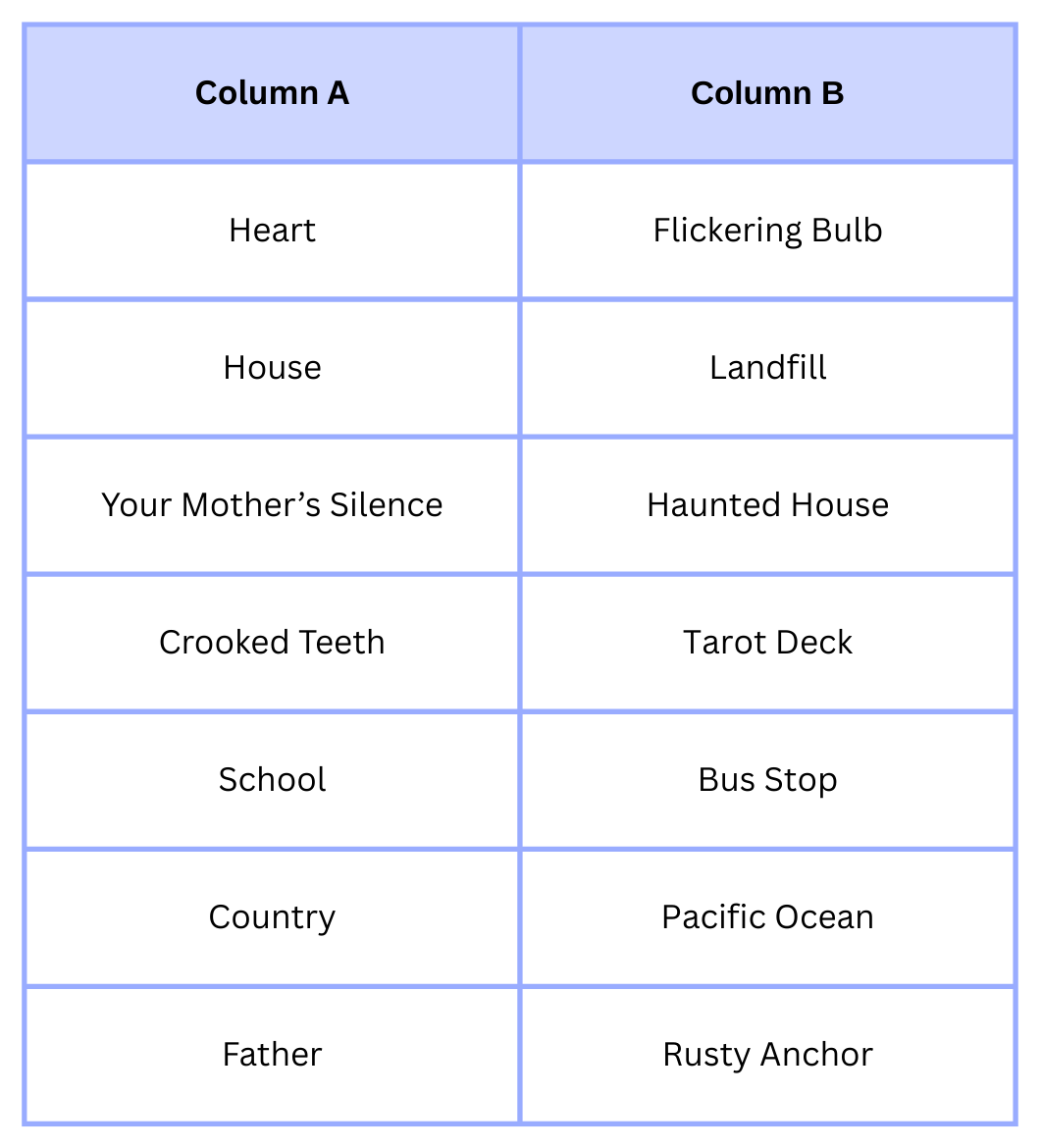

Make two columns: A & B.

In Column A, list things that are a part of you or your life (and any other tenor).

In Column B, list objects or images (or possible vehicles).

If you have trouble thinking of things, simply look around.

After you have your two columns, you can start playing with a metaphor combination. Take something from Column A and combine it with something in Column B to get a new metaphor.

Examples:

Your heart is a haunted house.

Your mother’s silence is the Pacific Ocean.

Your father is a flickering bulb.

Remember: don’t underestimate the material around you. I have come up with some of the best metaphors by looking out the window or around my office: Is your ego a staple remover? Your dreams a burnt pan?

#3. Thematic Diction

Once you have a metaphor that feels strong and complex enough that you could extend it over multiple lines (an extended metaphor), use thematic diction to amplify its impact.

Thematic diction refers to words that feel like they’re part of the same world or category.

Example: My mother’s silence is the Pacific Ocean.

Now create a list of words that complement this metaphor of the Pacific Ocean, eg:

Jetty

Wave

Crash

Low tide

Shoreline

Saltwater

Fish

Seaweed

Extended metaphor: My mother’s silence is the Pacific Ocean. A low tide of loneliness. Rising saltwater secrets she is thirsty to spill.

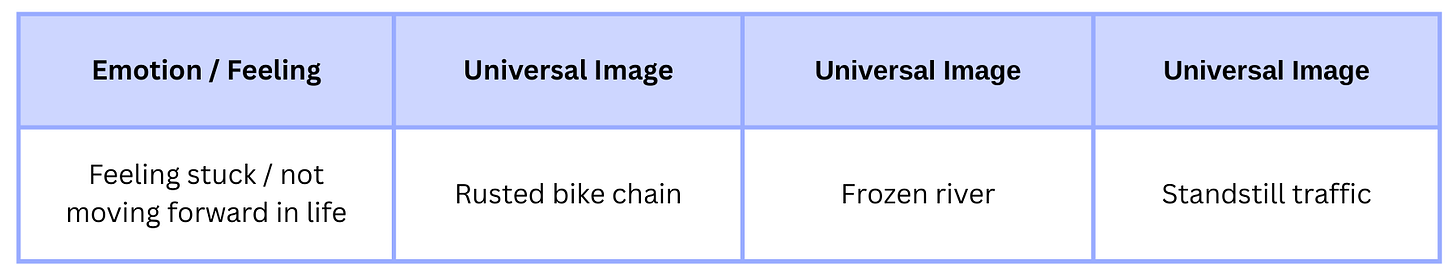

#4. Emotion to Image

Writing about emotions (such as love, fear, or anger) can be complicated because we all experience them differently, depending on factors like our individual experiences, age, and numerous other variables. However, when you take that emotion and pair it with something we all feel similar about, it can add clarity and immediate impact.

The image becomes a universal translation for the emotion, bringing the reader closer to the speaker’s experience.

Example: For those who have been waiting to quit the job, the man, the lie you swig from every winter. The standstill traffic of excuses.

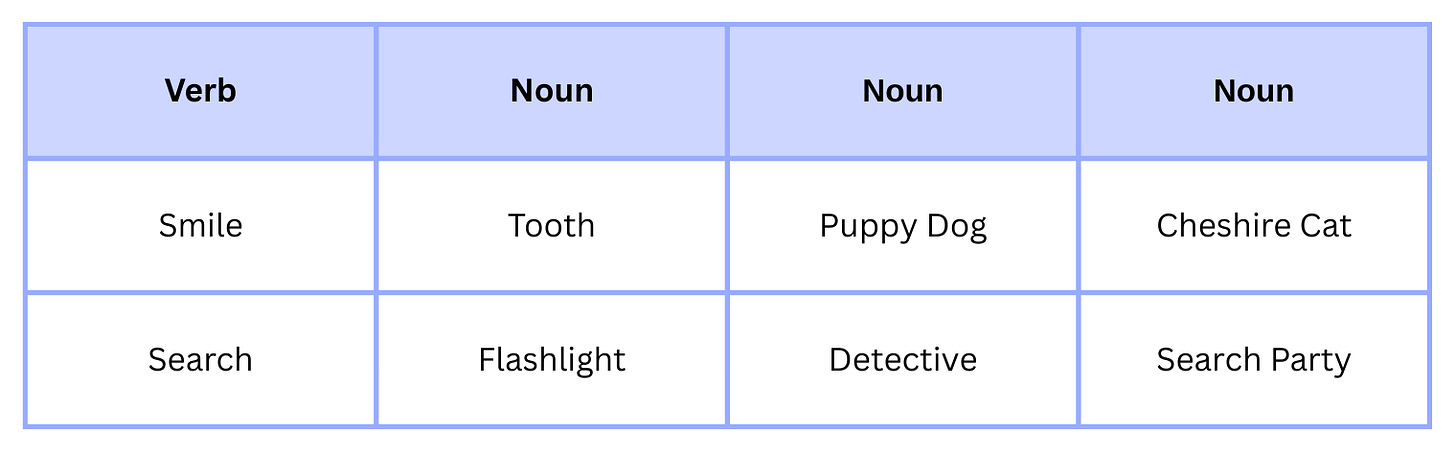

#5. Verbing Nouns

While metaphors are usually constructed of two parts, sometimes changing the syntax or parts of speech can provide an implied metaphor with a single word.

Anthimeria is the act of using one part of speech as another, such as using a noun as a verb. Play around with different nouns to see how, when used as a verb, they can create a metaphor.

Example:

How can they call us prey when we fang like this?

— Imani Davis, The Recital

Interpretation: We are stronger and sharper than given credit for. We know how to use our teeth.

Example: The bling of our hips don’t make them Cheshire cat the same.

Interpretation: Men don’t smile at us the way they used to.

Now that you have some new, exciting ways to craft fierce and fresh metaphors, try them out with the exercises below.

If you enjoyed this lesson, you’ll love the others too.

Some Metaphorical Writing Exercises:

Write a poem, essay, or scene where metaphor is used to explore a complicated relationship in your life. Read Edgar Kuntz’s Piano as an example.

Write a poem, essay, or scene about something complicated (war, love, loving your body) using a metaphor for something that is supposed to be fun (a trip to the beach, a bounce house, riding a horse). Read Jared Harél’s Sad Rollercoaster as an example.

Write a poem, essay, or scene that explores one of the metaphors you created by combining List A and List B. Use thematic diction throughout the poem to establish an extended metaphor. Or take one of the metaphors and use it as a prompt. For example: My house is a silent film. Read Hieu Minh Nguyen's Buffet Etiquette as an example.

Write a poem where you use an element of the natural world as a metaphor for a large concept (love, fear, justice). Read Chelsea B. DesAutels' City Lake as an example.

Questions? Comments? Responses? Let’s Chat!

Also feel free to post what you wrote in the comments so we can “ohhhh” and “ahhhh” over your beautiful metaphors.

I’ll let you know what I love about your piece and why :)

In the next Crafting Fierce and Flawless Figurative Language lesson, we will use imagery to craft writing so real it feels like your reader can walk around — touch, taste, see, hear, smell — the world of our words. Learn five surefire techniques on how to create images so unforgettable they will stay with your readers long after they have left the page.

Paid subscribers will receive a brand new lesson every Wednesday in August, so join in to learn more ways to transform your words from idea to impact!

Dropping a comment to say this installment was EXCELLENT. Excellent job. My heart is a singing bird at the end of a rainy day after reading.

Great first lesson! Here's my extended metaphor from the two columns:

I used to believe that truth was solid, unmovable, like granite. Now it’s more of a complicated calculus. A negative raised to an even power becomes positive, a fraction divided by the denominator gets you whole numbers. The equation balances. Both sides amount to the same thing - yet they appear completely different. Truth isn't a concrete rock; it's the changeable chameleon hiding on the rock's surface.